| Previous: Loops and Tables | Next: |

Variable Scope and Sharing Data 🔗

Introduction 🔗

Over the past few lessons, I’ve been writing about “local” and “global” variables, but I haven’t given them a proper explanation. I also haven’t explained why the Lua Scenario Template disables global variables, even though it makes trying things out in the console inconvenient. I’ll explain all that in this lesson.

Because it is a related subject, we will also see how to share data and functions between files. Having multiple files is convenient for organizing our code. As part of this, we’ll see how to use the object.lua file to make our code more readable. We will also build a counting function and an event to “capture” enemy triremes as part of this discussion.

We will be interpreting some errors as part of this discussion, and we will learn how to use the “short circuiting” feature of the and and or operators to prevent “index a nil value” errors.

Almost by accident, the data sharing discussion will lead us to an explanation of how to use “methods,” which we haven’t yet taken an opportunity to discuss.

Variable Scope Gone Wrong 🔗

A variable’s scope is the term used for the part of a program that can access or change the value stored by that variable. It is very common for a file to have multiple variables with the same name. Variable names like unit, tribe, or city can appear dozens of times in a large file with lots of events or functions. By limiting the scope of a variable, we can reuse variable names within a file (or between files) without creating a conflict.

Let’s create an example conflict to illustrate what can go wrong if a variable’s scope is too expansive. Open VS Code, and the Lua folder. When the time comes, load the saved game in the Original folder that you’ve been using to run scripts. This example will involve global variables.

Create a new file, scope.lua.

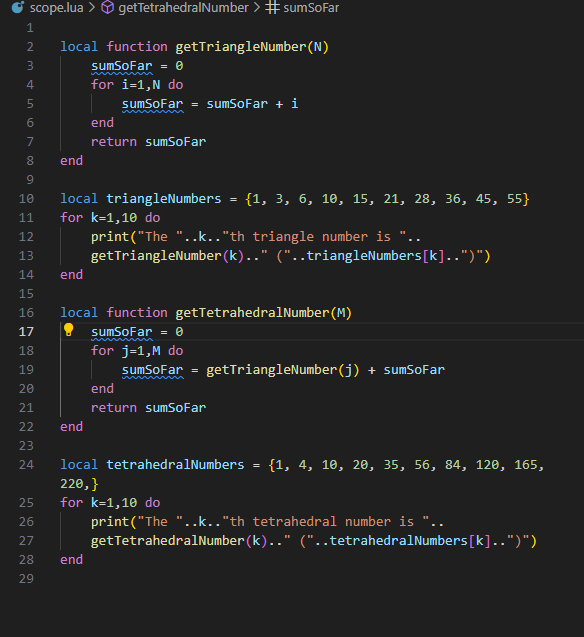

In math, the $N^{th}$ triangle number is defined to be $T_{N} = 1 + 2 + 3 + … + (N-1) + N $, which is to say, the sum of the first $N$ counting numbers. There is a formula for the triangle numbers, but we will write a straightforward function that adds all these numbers up:

local function getTriangleNumber(N)

sumSoFar = 0

for i=1,N do

sumSoFar = sumSoFar + i

end

return sumSoFar

end

Since we’re creating an example with a scope conflict, we omit the local designation of sumSoFar, so that its scope goes beyond the function getTriangleNumber. The logic of this code is very similar to that of the factorial function from the last lesson.

We can get a list of triangle numbers from the Wikipedia page and put the list in a table. Then, we can compare the numbers our function generates with the actual numbers.

local triangleNumbers = {1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28, 36, 45, 55}

for k=1,10 do

print("The "..k.."th triangle number is "..

getTriangleNumber(k).." ("..triangleNumbers[k]..")")

end

Now, it turns out that the $M^{th}$ tetrahedral number is the sum of the first $M$ triangle numbers, so we can write this function:

local function getTetrahedralNumber(M)

sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,M do

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

end

return sumSoFar

end

And check that it works with the following list and loop:

local tetrahedralNumbers = {1, 4, 10, 20, 35, 56, 84, 120, 165, 220,}

for k=1,10 do

print("The "..k.."th tetrahedral number is "..

getTetrahedralNumber(k).." ("..tetrahedralNumbers[k]..")")

end

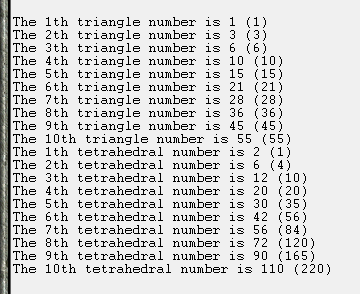

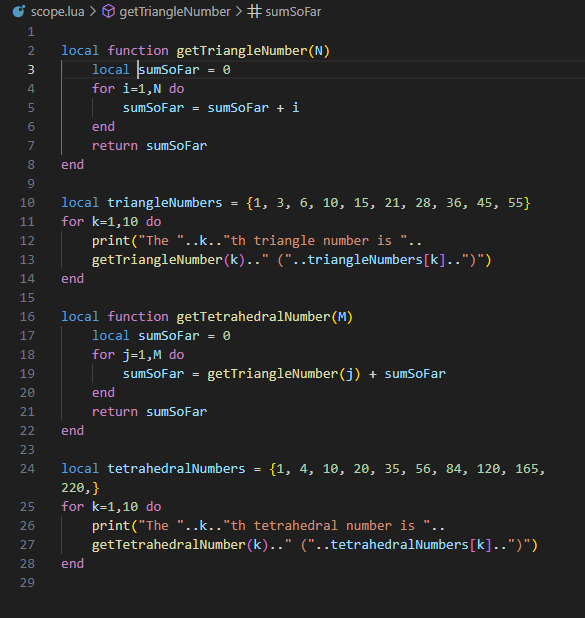

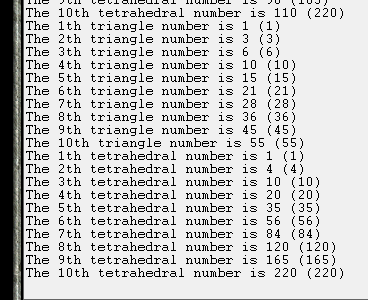

The triangle numbers are correct, but the tetrahedral numbers are not. To prove this is an issue with variable scope, we can add local to the definition of sumSoFar and try again:

So, what was the problem? The problem is that both getTriangleNumber and getTetrahedralNumber were sharing the same variable sumSoFar. Look again at getTriangleNumber:

local function getTriangleNumber(N)

sumSoFar = 0

for i=1,N do

sumSoFar = sumSoFar + i

end

return sumSoFar

end

When getTriangleNumber is executed, the first thing it does is set sumSoFar to 0. It then updates sumSoFar until the variable has taken on the value of the Nth triangle number. During the execution of getTriangleNumber, sumSoFar is first set to 0, then only updated when the function’s logic calls for it. So, calling this function returns the value of the Nth triangle number and causes sumSoFar to take on that value.

Now, let’s evaluate getTetrahedralNumber for M = 2, knowing that getTriangleNumber changes the value of sumSoFar. The comments at the top of the code represent the current value of variables:

local function getTetrahedralNumber(M)

sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,M do

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

end

return sumSoFar

end

The first line:

-- M = 2

sumSoFar = 0

This is a straightforward variable assignment, so proceed to the next line

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,M do

Substitute 2 for M

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,2 do

Now, proceed to the next line, where j will be 1 because of the loop:

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

-- j = 1

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

We need to evaluate getTriangleNumber(j), so replace j with 1:

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

-- j = 1

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(1) + sumSoFar

Now, getTriangleNumber(1) is evaluated, which does two things. First, getTriangleNumber(1) is replaced with 1, and the sumSoFar variable is updated to be 1

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 1

-- j = 1

sumSoFar = 1 + sumSoFar

Next, replace sumSoFar on the right hand side with 1. This is the point where the code logic breaks. getTetrahedralNumber was written based on the logic that sumSoFar would be 0 at this point, but it has been “unexpectedly” changed to 1.

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 1

-- j = 1

sumSoFar = 1 + 1

sumSoFar = 2

Now, sumSoFar is set to 2 and we proceed ot the next line.

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 2

-- j = 1

end

This is the end of the loop body, so start over, incrementing j to 2:

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 2

-- j = 2

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(2) + sumSoFar

getTriangleNumber(2) evaluates as 3, so replace the function call and update sumSoFar:

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 3

-- j = 2

sumSoFar = 3 + sumSoFar

Now, replace the right hand side sumSoFar with the current value of the variable:

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 3

-- j = 2

sumSoFar = 3 + 3

sumSoFar = 6

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 6

-- j = 2

end

At this point, the loop ends since j = 2 is the maximum value for j.

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 6

-- j = 2

return sumSoFar

return 6

And so, 6 is returned, which is incorrect. If getTriangleNumber didn’t modify sumSoFar for getTetrahedralNumber, the computation would work correctly. Here’s an demonstration of the computation.

-- M = 2

local sumSoFar = 0

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,M do

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,2 do

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

-- j = 1

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

-- j = 1

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(1) + sumSoFar

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

-- j = 1

sumSoFar = 1 + sumSoFar

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 0

-- j = 1

sumSoFar = 1 + 0

sumSoFar = 1

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 1

-- j = 1

end

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 1

-- j = 2

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(2) + sumSoFar

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 1

-- j = 2

sumSoFar = 3 + sumSoFar

sumSoFar = 3 + 1

sumSoFar = 4

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 4

-- j = 2

end

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 4

return sumSoFar

-- M = 2

-- sumSoFar = 4

return 4

And, the second tetrahedral number is, in fact, 4.

This example illustrates one of the reasons why global variables are disabled in the Lua Scenario Template. If you forget to write local before your variable when you define and initialize it, by default Lua sees that not as a mistake, but as an indication that you wanted to use a global variable in that instance. So, because we “forgot” to write local a couple times, these very simple functions didn’t behave as expected, and mistake which causes the error is not obvious.

Determining a Variable’s Scope 🔗

Now that we have an example of the problems that arise when a variable’s scope is too large, let’s explore the rules that determine a variable’s scope. These rules are mostly described if understand the concept of a code block.

A code block is a portion of code that begins with for, if, while, or function, and finishes with a corresponding end. (Lua has a repeat-until loop structure that I will discuss in a future lesson, which is also a code block.) Additionally, the entire file is considered a code block as well.

The idea of a code block will be clearer if we look at the contents of a couple files and point out the code blocks.

Here is the current scope.lua code:

local function getTriangleNumber(N)

local sumSoFar = 0

for i=1,N do

sumSoFar = sumSoFar + i

end

return sumSoFar

end

local triangleNumbers = {1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28, 36, 45, 55}

for k=1,10 do

print("The "..k.."th triangle number is "..

getTriangleNumber(k).." ("..triangleNumbers[k]..")")

end

local function getTetrahedralNumber(M)

local sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,M do

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

end

return sumSoFar

end

local tetrahedralNumbers = {1, 4, 10, 20, 35, 56, 84, 120, 165, 220,}

for k=1,10 do

print("The "..k.."th tetrahedral number is "..

getTetrahedralNumber(k).." ("..tetrahedralNumbers[k]..")")

end

The following code blocks exist in the file code (in addition to the file itself):

local function getTriangleNumber(N)

local sumSoFar = 0

for i=1,N do

sumSoFar = sumSoFar + i

end

return sumSoFar

end

for i=1,N do

sumSoFar = sumSoFar + i

end

for k=1,10 do

print("The "..k.."th triangle number is "..

getTriangleNumber(k).." ("..triangleNumbers[k]..")")

end

local function getTetrahedralNumber(M)

local sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,M do

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

end

return sumSoFar

end

for j=1,M do

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

end

for k=1,10 do

print("The "..k.."th tetrahedral number is "..

getTetrahedralNumber(k).." ("..tetrahedralNumbers[k]..")")

end

The file twelveDays.lua has the following code blocks:

local dayInfo = {

[1] = {day="first", line="And a partridge in a pear tree."},

[2] = {day="second", line="Two turtle doves,"},

[3] = {day="third", line="Three French hens,"},

[4] = {day="fourth", line="Four calling birds,"},

[5] = {day="fifth", line="Five gold rings,"},

[6] = {day="sixth", line="Six geese a-laying,"},

[7] = {day="seventh", line="Seven swans a-swimming,"},

[8] = {day="eighth", line="Eight maids a-milking,"},

[9] = {day="ninth", line="Nine ladies dancing,"},

[10] = {day="tenth", line="Ten lords a-leaping,"},

[11] = {day="eleventh", line="Eleven pipers piping,"},

[12] = {day="twelfth ", line="Twelve drummers drumming,"},

}

local function makeVerse(verse)

if verse == 1 then

print("On the first day of Christmas, my true love sent to me")

print("A partridge in a pear tree.")

return

end

print("On the "..dayInfo[verse].day.." day of Christmas, my true love sent to me")

for i=verse,1,-1 do

print(dayInfo[i]["line"])

end

end

local function printTwelveDaysOfChristmas()

for i=1,12 do

print("")

makeVerse(i)

end

end

printTwelveDaysOfChristmas()

local function makeVerse(verse)

if verse == 1 then

print("On the first day of Christmas, my true love sent to me")

print("A partridge in a pear tree.")

return

end

print("On the "..dayInfo[verse].day.." day of Christmas, my true love sent to me")

for i=verse,1,-1 do

print(dayInfo[i]["line"])

end

end

if verse == 1 then

print("On the first day of Christmas, my true love sent to me")

print("A partridge in a pear tree.")

return

end

for i=verse,1,-1 do

print(dayInfo[i]["line"])

end

end

local function printTwelveDaysOfChristmas()

for i=1,12 do

print("")

makeVerse(i)

end

end

for i=1,12 do

print("")

makeVerse(i)

end

The scope of a local variable is the code block that it is defined in, starting at the line containing local, except for any smaller code blocks within the block, where a local variable with the same name is also defined.

A global variable has its scope everywhere, except in code blocks where a local variable of the same name is defined.

Those definitions were a mouthful, so let’s look at some examples. Comment out the triangular/tetrahedral number code and add this code:

local i = 7

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

for i=2,2 do

print("for i:"..i.."(2)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

if true then

local i = 3

i = i + 2

print("if i: "..i.."(5)")

if false then

else

local i = -3

i = i + 1

print("else i: "..i.."(-2)")

end

print("if i: "..i.."(5)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

local function aFunction(i)

i = i + 3

print("function i: "..i.."(11)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

aFunction(8)

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

for j=1,1 do

i = i+1

print("file i: "..i.."(8)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(8)")

if true then

if false then

else

i = i - 2

print("file i: "..i.."(6)")

end

i = i+1

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

end

local function anotherFunction()

i = i+2

print("file i: "..i.."(9)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

anotherFunction()

print("file i: "..i.."(9)")

You can run this code to see that the values in parentheses are, in fact, the values of i at that particular point. I’ll go through the code, and explain why i takes on these values.

local i = 7

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

Here, we define i in the code block of the entire file (well, all lines after this point in any case) and immediately verify that it is 7.

for i=2,2 do

print("for i:"..i.."(2)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

The i defined inside the for loop is local to the loop, so when we ask for i within this loop, we get the “for loop i”, which has a value of 2. (The body of this loop executes only once.)

Once we’re out of the loop, i once again corresponds to the “file i”, which has a value of 7.

if true then

local i = 3

i = i + 2

print("if i: "..i.."(5)")

Inside the body of this if statement, a new i is defined. i = i + 2 refers to the i that has been defined within the if statement. This is also true of the print line, where the “if i” now has a value of 5.

if false then

else

local i = -3

i = i + 1

print("else i: "..i.."(-2)")

end

print("if i: "..i.."(5)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

In this if statement, we proceed to the else section. Here, yet another i is defined, calculated upon, and this time ends up with a value of -2.

After the first end, we’re back to the “if i” version of i, which still has a value of 5, since it wasn’t the i that changed.

After the second end, we’re back to looking at the “file i”, which is unchanged.

local function aFunction(i)

i = i + 3

print("function i: "..i.."(11)")

end

Here, we define aFunction, which has a parameter i, which is a local variable within the function. Note that this was just a function definition, so nothing was printed yet.

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

aFunction(8)

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

Defining a function leaves “file i” unchanged.

Executing aFunction with starts by giving “function i” a value of 8, then adding 3 in order to get a value of 11, which is printed at this point.

Since “function i” is different from “file i”, the later still has a value of 7.

for j=1,1 do

i = i+1

print("file i: "..i.."(8)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(8)")

This time, the loop variable is j, so changing the value of i actually changes “file i”, because there is no “loop i” that takes precedence. Since this loop only executes the body once, “file i” still has a value of 8 after the loop.

if true then

if false then

else

i = i - 2

print("file i: "..i.."(6)")

end

i = i+1

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

end

Neither of these smaller code blocks defines a local version of i, so “file i” is the variable that has calculations performed on it, and is the i referenced in the print lines.

local function anotherFunction()

i = i+2

print("file i: "..i.."(9)")

end

print("file i: "..i.."(7)")

This time, the function definition doesn’t define i as a parameter, so it changes the “file i” when computing i = i + 2. However, at this point “file i” is still 7, since defining a function doesn’t execute it.

anotherFunction()

print("file i: "..i.."(9)")

At this point, executing anotherFunction increases “file i” to 9. anotherFunction prints this new value, then the print line does so again.

Don’t worry about memorizing the details of scope, because it most of the time it doesn’t really matter. Instead of remembering the difference between “file i” and “if i”, just name one of them j or ifI. Your code will be much easier to read and understand that way.

In practice, the fact that local variables work the way they do is typically a source of protection for your code, rather than a source of bugs. When you use local to create “if i”, you don’t have to worry about whether there is some “file i” in your code that you’ve forgotten about.

There is one caveat to the above assertions. You have to make sure to define your local variable in the largest code block that you intend to use it in. That is, the following is incorrect:

if someValue then

local a = 1

else

local a = 2

end

print(a)

The “if a” and “else a” are only valid within the if-else statement, so print(a) either prints the global variable version of a, or produces an error in the Lua Scenario Template.

The proper way to write this section of code is:

local a = nil

if someValue then

a = 1

else

a = 2

end

print(a)

We will use this kind of mistake in a future example, where we will see just how much trouble global variables can cause.

The Treacherous Global Variable 🔗

This section title is a little over the top, but only a little. Global variables can turn errors that should be easy to detect and fix into subtle and inconsistent bugs, as we saw earlier and will see again shortly.

The global variables are actually stored in a table. If you like, you can reference it with the variable name _G. So, if you wanted, you could write _G.print or _G.someKey and use it like any other table.

However, we don’t write _G.print, we just write print. The reason is that whenever we write a variable name, Lua checks if that name corresponds to a local variable in scope. If it doesn’t, then Lua converts the variable name to a string and checks the global table _G for the value associated with the key. If we want, say, the print function or the civ table of functions then everything’s great.

The problems arise when we use a global variable by mistake. Since _G is a table, it will return nil for any key that doesn’t already have an associated value. If we type myvariable instead of myVariable, Lua dutifully assumes that we wanted to access the global variable myvariable and not that we’ve made a typo. Instead of generating an error that we can notice and fix, Lua forces us to detect that our code isn’t doing what we want it to do because somewhere that we want to use the value of myVariable, we’re just getting nil because we accidentally typed myvariable.

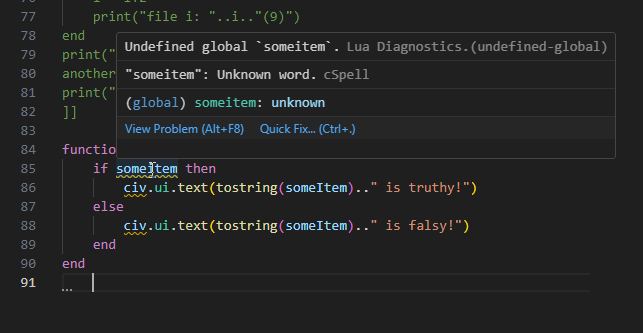

Here is an example. Comment out the previous code in scope.lua and add this code:

function isTruthy(someItem)

if someitem then

civ.ui.text(tostring(someItem).." is truthy!")

else

civ.ui.text(tostring(someItem).." is falsy!")

end

end

This function is supposed to determine if someItem is truthy or falsy, and show a corresponding text box. However, there is a misspelling someitem in the code.

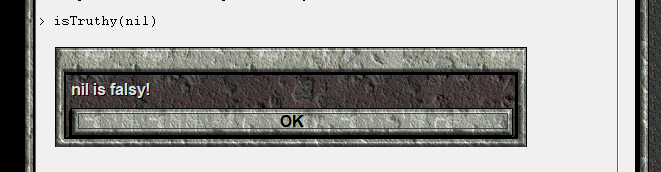

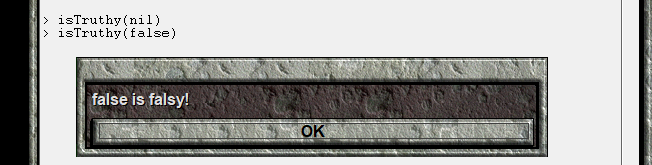

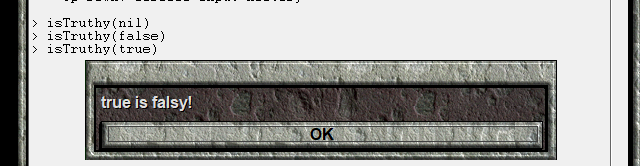

The Lua Language Server catches someitem as a possible mistake, but let’s see what happens when we run the function. Save and load the script to register the function. Since isTruthy is global on purpose, we can access it from the console to test:

Well, true is definitely not falsy. What we want in this situation is for Lua to generate an error, saying that someitem is not a registered variable name. This would alert us to the existence of the typo. Instead, Lua just gets the "someitem" entry in _G, which is nil, and it is up to us to notice that our function is not working properly. That’s easy in this example, but even noticing there is a problem can quickly become difficult in a complicated event.

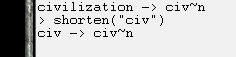

This Lua behaviour can even create bugs that sometimes cause errors, while not causing them at other times. Add the following function to scope.lua and load the script again.

function shorten(str)

if string.len(str) <= 5 then

local shortString = str

else

shortString = string.sub(str,1,3).."~"..string.sub(str,-1,-1)

end

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

end

This function is supposed to “shorten” a string str to a five character representation, and print the original string and the shortened form. Note that the function parameter is called str instead of string. This isn’t to save effort typing, but rather because string is already a global variable containing a table of functions for string manipulation.

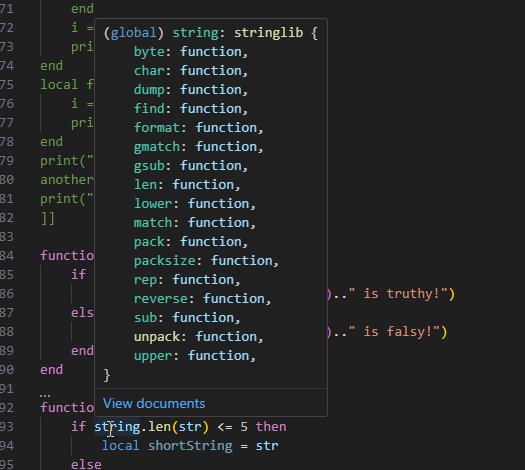

Hovering over string can get you the list of string functions:

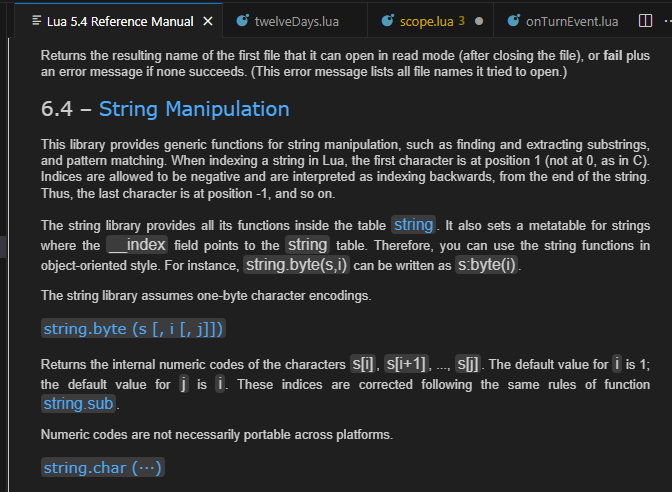

And you can find out more by clicking “view documents”:

if string.len(str) <= 5 then

local shortString = str

else

The function string.len returns the number of characters in the string (its length). If it is less than or equal to 5, the shortString is the same as str.

else

shortString = string.sub(str,1,3).."~"..string.sub(str,-1,-1)

end

If the length of str is more than 5, the shortString is created using the first 3 characters of str, a ~ character, and the last character of the string.

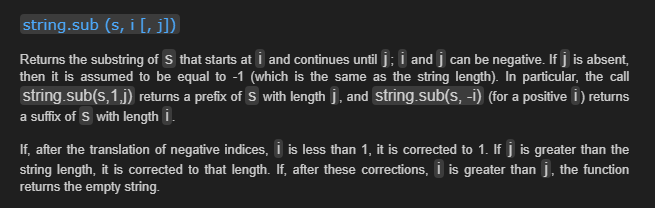

The function string.sub returns a “substring” of the provided string. Positive numbers for the second and third arguments count characters from the beginning of the string. Negative numbers mean to count from the end. Here’s the documentation:

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

Finally, we print the original string and an arrow pointing towards the shortened form.

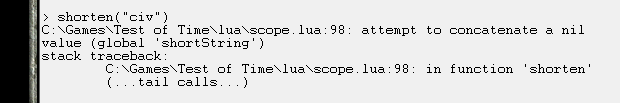

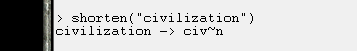

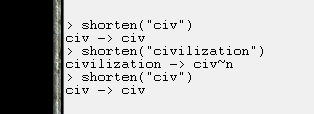

Now, in the Lua Console, call the shorten function on a string with five or fewer characters. Here’s an example using "civ" and the result:

The error “attempt to concatenate a nil value” means that our code is trying to join two strings together with .., but a variable that is supposed to have a string (or number) is in fact nil, and so can’t be concatenated.

Next, shorten a longer word, say "civilization":

That works as expected. However, if we again try shorten("civ"), we don’t get an error this time:

This isn’t the correct way to shorten "civ", but this time no error was generated. In this case, having global variables active have turned a simple mistake into code that, for the same argument, sometimes generates an error and sometimes does not. I have actually made this kind of mistake, and had to fix it later, once someone noticed it.

So, what happened? The first time shorten("civ") was called, "civ" was assigned to “local shortString” and then promptly “forgotten” as the Lua Interpreter moved beyond that code block. Then, the line

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

asked for “global shortString”, which was nil, and, therefore, caused an error.

After that, we called shorten("civilization") and, the line

shortString = string.sub(str,1,3).."~"..string.sub(str,-1,-1)

assigned "civ~n" to “global shortString”, since the local keyword was absent. The line

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

worked as expected, since it also references “global shortString”.

Finally, shorten("civ") was called again, and "civ" was once again assigned to “local shortString”, and once again “forgotten”.

However, upon reaching the line

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

“global shortString” is referenced once again, but this time it has a value of "civ~n". Since that is a string which can be concatenated, no error is produced.

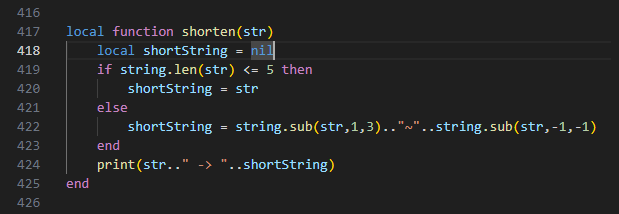

Let’s spend a bit of time improving the shorten function. First, let’s fix the error by defining shortString before the if statement:

function shorten(str)

local shortString = nil

if string.len(str) <= 5 then

shortString = str

else

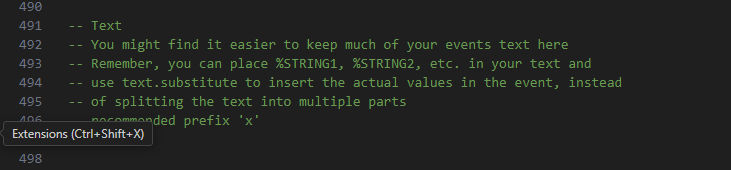

shortString = string.sub(str,1,3).."~"..string.sub(str,-1,-1)

end

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

end

Since we’re here, let’s take note of a trick to allow us to rename str as string. For the existing references to the string functions, we will prepend _G. so that the reference to the global variables table is explicit instead of implicit:

function shorten(str)

local shortString = nil

if _G.string.len(str) <= 5 then

shortString = str

else

shortString = _G.string.sub(str,1,3).."~".._G.string.sub(str,-1,-1)

end

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

end

Now, since we’re not using the “global string” variable in this function, we can rename str to string without causing problems.

function shorten(string)

local shortString = nil

if _G.string.len(string) <= 5 then

shortString = string

else

shortString = _G.string.sub(string,1,3).."~".._G.string.sub(string,-1,-1)

end

print(string.." -> "..shortString)

end

If we reload scope.lua and run our tests again, we see that they now work correctly.

Disabled Global Variables 🔗

I have hopefully convinced you by this point that disabling global variables is a good idea. So, now, let’s work within the ClassicRome scenario again.

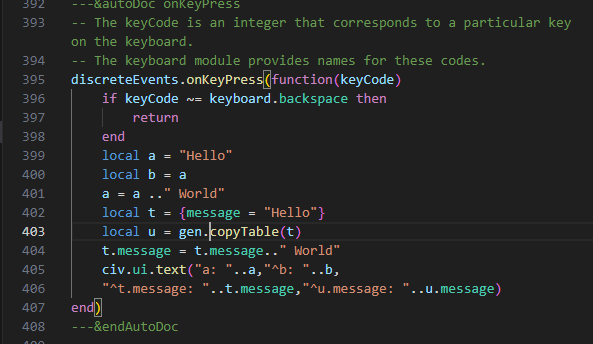

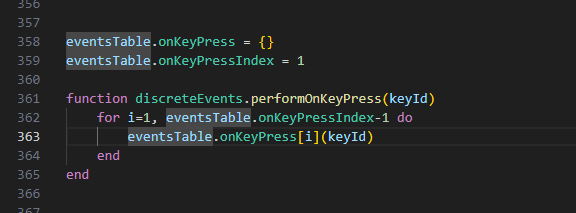

In the last lesson, we made a Key Press event in discreteEvents.lua to test how tables work:

Now, we’re going to change contents of this “event” to test out the bad code that we looked at earlier. Let’s begin with the triangle and tetrahedral numbers. Remove the existing key press event, and replace it with this code:

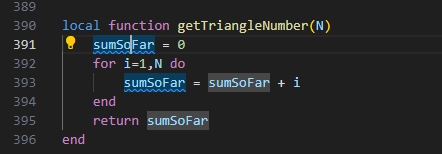

local function getTriangleNumber(N)

sumSoFar = 0

for i=1,N do

sumSoFar = sumSoFar + i

end

return sumSoFar

end

local function getTetrahedralNumber(M)

sumSoFar = 0

for j=1,M do

sumSoFar = getTriangleNumber(j) + sumSoFar

end

return sumSoFar

end

local triangleNumbers = {1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28, 36, 45, 55}

local tetrahedralNumbers = {1, 4, 10, 20, 35, 56, 84, 120, 165, 220,}

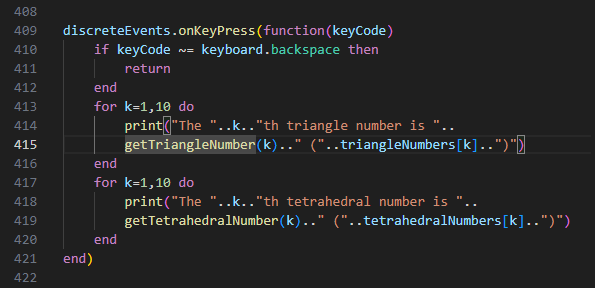

discreteEvents.onKeyPress(function(keyCode)

if keyCode ~= keyboard.backspace then

return

end

for k=1,10 do

print("The "..k.."th triangle number is "..

getTriangleNumber(k).." ("..triangleNumbers[k]..")")

end

for k=1,10 do

print("The "..k.."th tetrahedral number is "..

getTetrahedralNumber(k).." ("..tetrahedralNumbers[k]..")")

end

end)

Note that I eliminated the nearby comments. They were mostly there for information. The ---&autoDoc and ---&endAutoDoc comments are there for me to more easily build this website’s documentation from the template, and you don’t need to keep them in your scenarios.

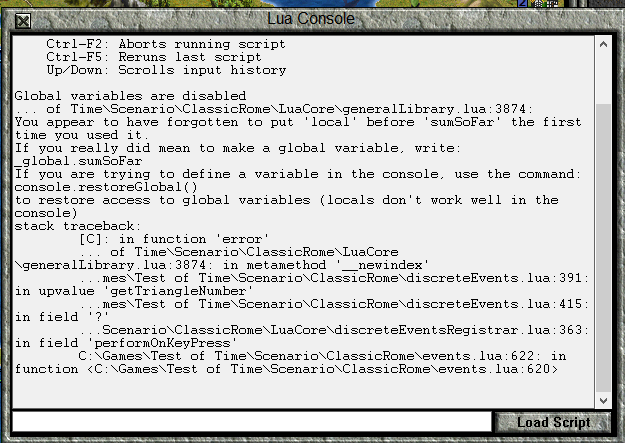

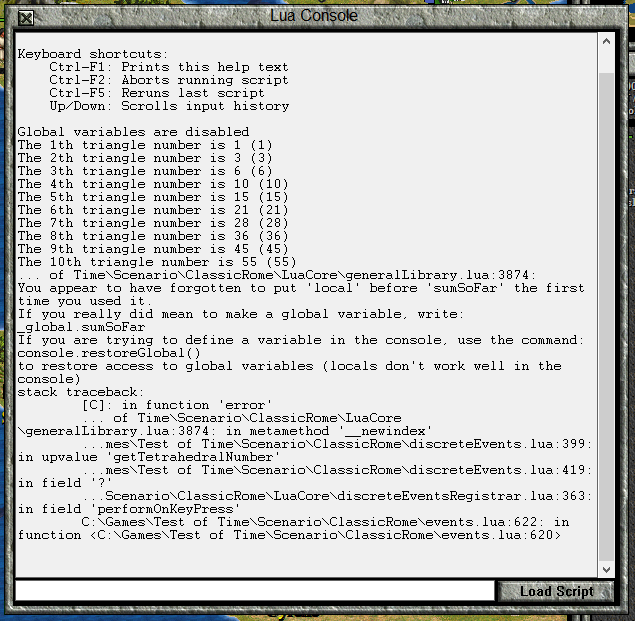

Save the discreteEvents.lua file, load a saved game in the ClassicRome folder, and press backspace. We get the following error:

Let’s examine the error to understand it.

... of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\LuaCore\generalLibrary.lua:3874:

This is telling us that Lua “discovered” the error in the LuaCore\generalLibrary.lua file at line 3874. The reason for this is that the code I use to disable global variables is written in the General Library. The General Library contains several functions that generate errors like this. If an error with a customised message is triggered in generalLibrary.lua, another part of the Template is probably just using error checking code that is provided by the General Library, and the actual error is connected to that section. Later on in the error message, you will get information about the other possible locations of the error.

You appear to have forgotten to put 'local' before 'sumSoFar' the first time you used it.

If you really did mean to make a global variable, write:

_global.sumSoFar

If you are trying to define a variable in the console, use the command:

console.restoreGlobal()

to restore access to global variables (locals don't work well in the console)

This is my custom error message. It suggests three possible problems that might cause the error.

The first is that we forgot to put the local keyword before the sumSoFar variable, the first time we used it (this is, in fact, our mistake).

A second possibility is that we really wanted to make a global variable. Since ordinary global variables are disabled, the Lua Scenario Template provides an alternative with the _global table. I’ll explain that later in this lesson.

The last possibility is that you’re trying to do some work in the console, where local variables don’t work. If that’s the case, you can enable global variables with the console.restoreGlobal() command.

stack traceback:

[C]: in function 'error'

... of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\LuaCore\generalLibrary.lua:3874: in metamethod '__newindex'

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:391: in upvalue 'getTriangleNumber'

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:415: in field '?'

...Scenario\ClassicRome\LuaCore\discreteEventsRegistrar.lua:363: in field 'performOnKeyPress'

C:\Games\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\events.lua:622: in function <C:\Games\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\events.lua:620>

The “stack traceback” is the list of files and lines associated with the error. Starting at the line with the code that caused the error, Lua provides the part of the program that “asked” for the error to be executed.

[C]: in function 'error'

... of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\LuaCore\generalLibrary.lua:3874: in metamethod '__newindex'

This says that the error function caused the error at generalLibrary.lua line 3874. A “metamethod” is terminology associated with Lua “metatables.” A “metatable” is a way to change the ordinary rules for how tables work. I won’t be explaining how to use them for a while, but for now all you need to know is that I used a “metatable” to make the _G table create an error when you try to access a nil value in the table.

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:391: in upvalue 'getTriangleNumber'

This tells us that the program was also at discreteEvents.lua line 391 at the time of the error. (You might have a different line in your file.) “in upvalue ‘getTriangleNumber’” means that the error took place while executing a local variable getTriangleNumber. Don’t worry about remembering the meaning of “upvalue,” or, later, “field.” I had to lookup what “upvalue” meant while writing this lesson. All you really need to pay attention to is the function name provided, if there is one.

This is the actual location of our error, since we failed to make sumSoFar a local variable.

Add the missing local to fix the error, but we’ll look through the rest of this error message, since, sometimes, the error might be in a different file.

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:415: in field '?'

This tells us that getTriangleNumber was called on line 415 of discreteEvents.lua, but there isn’t a name for the function. This makes sense, because its within an “anonymous function” that we supplied as the argument to discreteEvents.onKeyPress.

If this were a different kind of error, the mistake could have been here if we had supplied an invalid argument.

...Scenario\ClassicRome\LuaCore\discreteEventsRegistrar.lua:363: in field 'performOnKeyPress'

The next level up for the error is in LuaCore\discreteEventsRegistrar.lua at line 363. Instead of “upvalue”, “field” is used, because the function is defined as a value within the discreteEvents table, assigned to the key performOnKeyPress.

It will sometimes be helpful to look at code within LuaCore directory files in order to determine the cause of an error. However, discreteEventsRegistrar.lua is not a useful file to check. The code in this file registers events. If you reach the point where you need to look inside this file for troubleshooting, ask for help in the Forum. I can help you find the bug in your code, or fix the bug in this file if I made a mistake programming it.

C:\Games\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\events.lua:622: in function <C:\Games\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\events.lua:620>

The “highest” level of the error is in events.lua at line 622, where the discreteEvents.performOnKeyPress is executed. I don’t know why the function beginning at line 620 is identified this time, while “field ?” was used earlier.

Like LuaCore\discreteEventsRegistrar.lua, if you’ve reached the point where you have to look inside events.lua in order to troubleshoot an error, it is time to seek help in the Forum, since this file is likely to be of limited use. Also, if there is an error in this file, I’d like to know about it to fix it.

The events.lua file is the file that Test of Time loads and runs when loading a saved game. All the other files in the template are executed based on instructions from this file. events.lua functions mostly as an organisational file, as well as including some behind the scenes work to create some “extra” execution points from the functions provided by the TOTPP.

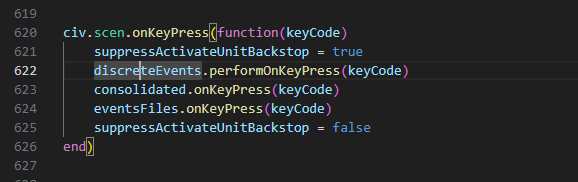

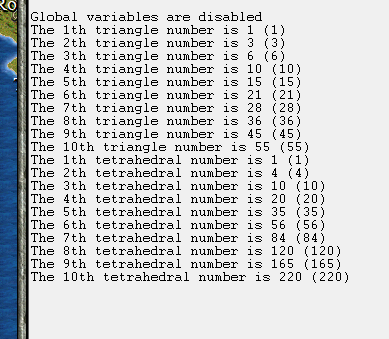

Now, add the missing local at line 391, save discreteEvents.lua, re-load the game, and press backspace once again. This time, the triangle numbers are printed, before we get this error:

Since this error is so similar to the last one, I won’t give instructions on how to correct it. If you have any trouble making the fix, you can ask for help in this thread.

Save the file, re-load the game, press backspace, and you should get the printed values of the first triangle and tetrahedral numbers printed:

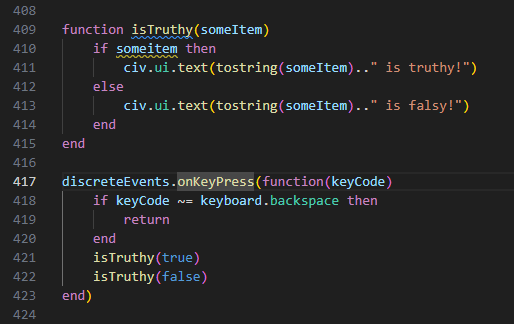

Next, we’ll look at the isTruthy function example. Change discreteEvents.lua so that the backspace key press event now looks like this:

function isTruthy(someItem)

if someitem then

civ.ui.text(tostring(someItem).." is truthy!")

else

civ.ui.text(tostring(someItem).." is falsy!")

end

end

discreteEvents.onKeyPress(function(keyCode)

if keyCode ~= keyboard.backspace then

return

end

isTruthy(true)

isTruthy(false)

end)

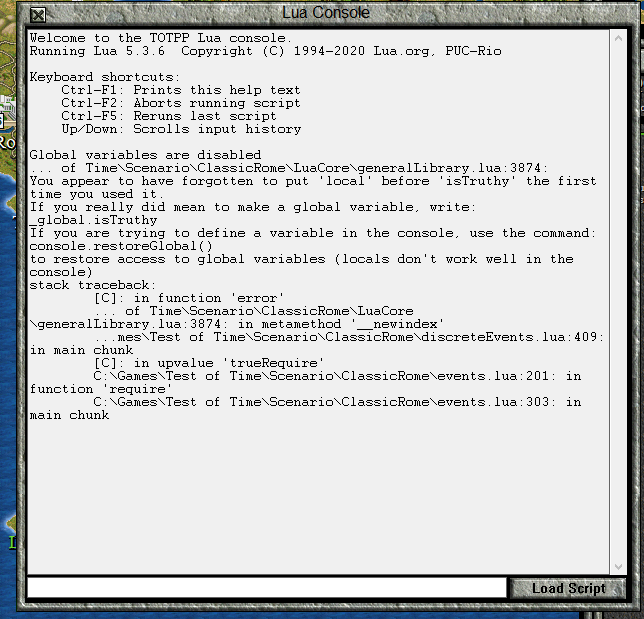

Save the file, and reload the game. During the process of loading the game, you will get this error:

This is the same error we’ve seen before, with the Lua Interpreter complaining that we’ve apparently forgotten to put local before isTruthy.

The reason this error is appearing now instead of when we press backspace is because the isTruthy function is created and assigned to a variable during the code initialisation which happens when a game is loaded.

This time, code in discreteEventsRegistrar.lua is not part of the stack traceback, because this didn’t occur during the execution of an event. Instead, it happened during a call to the require function, which allows Lua files to access information from other files. I will explain require later on in this lesson.

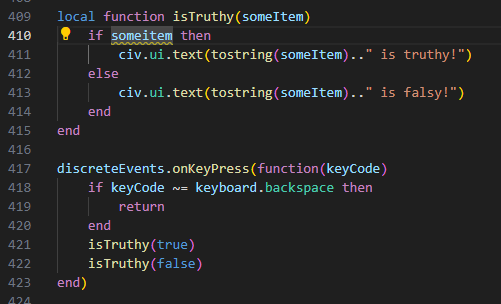

For now, change line 409 (or whatever it is in your version of discreteEvents.lua) to

local function isTruthy(someItem)

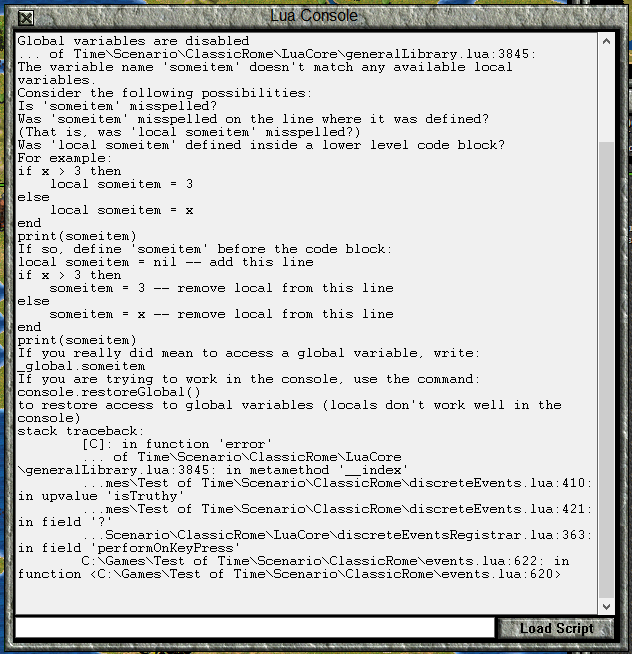

and try again to load the saved game. This time it should work, and you can press backspace. This error should appear:

Let’s break down the error message:

The variable name 'someitem' doesn't match any available local variables.

Consider the following possibilities:

This tells us that there is something wrong with the variable named someitem, because there is no local variable with that name. (Trying to access a global variable that doesn’t already exist triggers this error.) Next, a few possibilities and solutions are suggested.

Is 'someitem' misspelled?

The first possibility is that someitem is misspelled. In fact, that is what is causing the error in this case. If we think this is the mistake, the line in question will be one of the lines in the stack traceback, almost certainly the one after the generalLibrary.lua line. In this example, it would be discreteEvents.lua line 410.

Was 'someitem' misspelled on the line where it was defined?

(That is, was 'local someitem' misspelled?)

The next possibility is that the line that has the “global” variable is fine, but the line that defined it as a local variable was misspelled. The message suggests that there will be a line with local on it, but remember that local variables are also defined by function and loop parameters.

This time, the stack traceback will be a bit less helpful. The mistake is probably in the second file in the traceback (the one after LuaCore\generalLibrary.lua:3845: in metamethod ‘__index’) but you’ll have to work backwards from the line to find the mistake.

Was 'local someitem' defined inside a lower level code block?

For example:

if x > 3 then

local someitem = 3

else

local someitem = x

end

print(someitem)

If so, define 'someitem' before the code block:

local someitem = nil -- add this line

if x > 3 then

someitem = 3 -- remove local from this line

else

someitem = x -- remove local from this line

end

print(someitem)

This possibility is the one that the local variable was defined within a particular code block, but is needed outside of it. The example here is with an if statement, but, in principle, this could also happen in a loop. A version of this was the cause of the problems with the shorten function, which we’ll discuss soon.

If you really did mean to access a global variable, write:

_global.someitem

This reminds (or tells, since we haven’t discussed it yet) you how the Lua Scenario Template wants you to use global variables, if that is your intention.

If you are trying to work in the console, use the command:

console.restoreGlobal()

to restore access to global variables (locals don't work well in the console)

This tells you how to enable global variables for use in the console.

stack traceback:

[C]: in function 'error'

... of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\LuaCore\generalLibrary.lua:3845: in metamethod '__index'

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:410: in upvalue 'isTruthy'

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:421: in field '?'

...Scenario\ClassicRome\LuaCore\discreteEventsRegistrar.lua:363: in field 'performOnKeyPress'

C:\Games\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\events.lua:622: in function <C:\Games\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\events.lua:620>

The stack traceback tells us where to start our investigation, and line 410 of discreteEvents.lua is the prime place to start.

Looking at line 410, it is clear that someitem is a misspelling of someItem, the function parameter. If we fix this, save the code, load the game, and press backspace, we find that the isTruthy function works as desired.

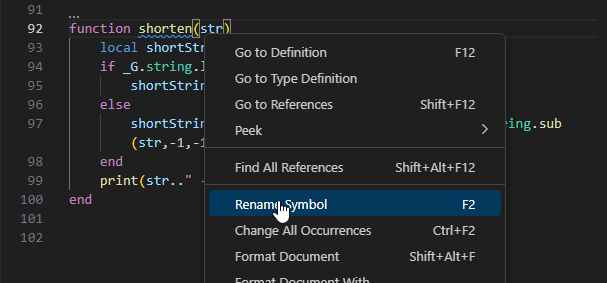

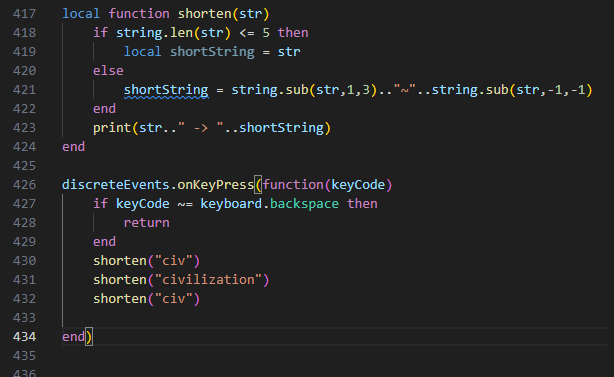

Now, change the key press event we’ve been working on in discreteEvents.lua as follows, in order to demonstrate the shorten example from earlier.

local function shorten(str)

if string.len(str) <= 5 then

local shortString = str

else

shortString = string.sub(str,1,3).."~"..string.sub(str,-1,-1)

end

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

end

discreteEvents.onKeyPress(function(keyCode)

if keyCode ~= keyboard.backspace then

return

end

shorten("civ")

shorten("civilization")

shorten("civ")

end)

I already made shorten a local function, but otherwise it is the version we looked at earlier that caused the errors.

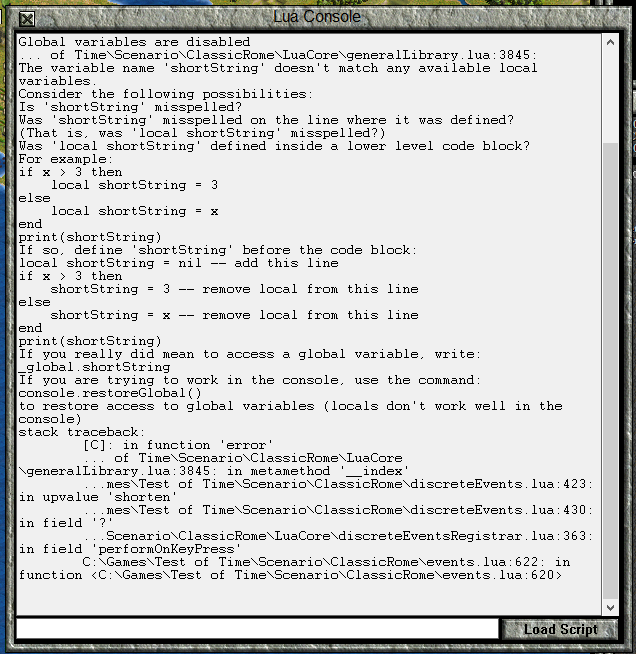

Save the file, reload the game, and press backspace.

The second line in the stack traceback is

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:423: in upvalue 'shorten'

This corresponds to the line

print(str.." -> "..shortString)

Since the beginning of the error tells us that shortString doesn’t match any local variables, we must look backwards in the code to find out why that is.

Upon inspection, all the previous references to shortString are within the if statement, and, therefore, not within the code block containing line 423. We must fix this by defining shortString before the if-else statement where it must be modified. We must also remove the local keyword from within the if statement.

You can check and see that this “event” now works properly. (This event prints to the console, so you’ll have to open it to see the result.)

require and Sharing Data Between Files 🔗

Up to this point, we’ve only worked in one .lua file at a time. Even though we’ve used code from LuaCore\discreteEventsRegistrar.lua, LuaCore\keyboard.lua and LuaCore\generalLibrary.lua, I have thus far simply told you what prefix to use and had you work in a file where those prefixes work. Now, I will show you how code is shared between files in Lua.

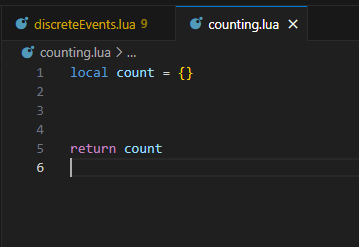

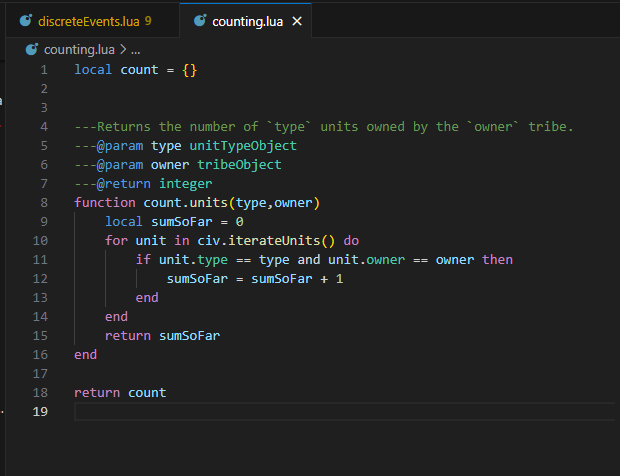

Let’s create a file called counting.lua, which we will put in the main ClassicRome folder. The counting.lua file will contain functions that count things, since that kind of functionality could be useful in several files, and we don’t want to duplicate effort.

The first thing we will do is create the count table:

local count = {}

Any value which we want to make available outside of counting.lua will have to be assigned to a key in the count table (or to a table which is itself assigned to the count table). The name of this table can be anything, but the Lua Language Server will use it in the documentation it generates.

We tell Lua that count is the table that we want to make available to other files with the line:

return count

This line must be at the end of the file. You can have extra spaces or comments after the return line, but no actual code to be executed.

Now, let’s create a function to count units of a particular type and owner:

---Returns the number of `type` units owned by the `owner` tribe.

---@param type unitTypeObject

---@param owner tribeObject

---@return integer

function count.units(type,owner)

local sumSoFar = 0

for unit in civ.iterateUnits() do

if unit.type == type and unit.owner == owner then

sumSoFar = sumSoFar + 1

end

end

return sumSoFar

end

Let’s first look at the Lua Language Server documentation comments:

---Returns the number of `type` units owned by the `owner` tribe.

---@param type unitTypeObject

---@param owner tribeObject

---@return integer

The first line is a brief description of what the function does. Since we’re not writing a module to share with others, a short explanation is probably sufficient, unless we find that we’re making mistakes using the function and we need a more detailed tooltip.

---@param type unitTypeObject and ---@param owner tribeObject identify the type and owner parameters as being unitTypeObjects and tribeObjects, respectively. The Lua Language Server (Lua LS) will warn us if we appear to be providing the wrong kind of data to this function.

---@return integer tells the Lua LS that this function returns an integer, which helps it detect if the returned value is being used incorrectly in a future calculation.

function count.units(type,owner)

This syntax is how we assign our newly created function to the "units" key of the count table. It is equivalent to

count.units = function(type,owner)

local sumSoFar = 0

Here, we define a variable to keep count of the units that we’ve found “so far” during the program.

for unit in civ.iterateUnits() do

This loop goes through every unit in the game, assigning the corresponding unitObject to the unit variable for evaluation in the loop body.

if unit.type == type and unit.owner == owner then

sumSoFar = sumSoFar + 1

end

end

If the type and owner of the unit match, then we’ve found a unit that must be counted, so we increment sumSoFar by 1.

return sumSoFar

end

Once we’ve finished the loop, the sumSoFar is the final total, since all units have been checked. Hence, we return the sumSoFar. Save counting.lua.

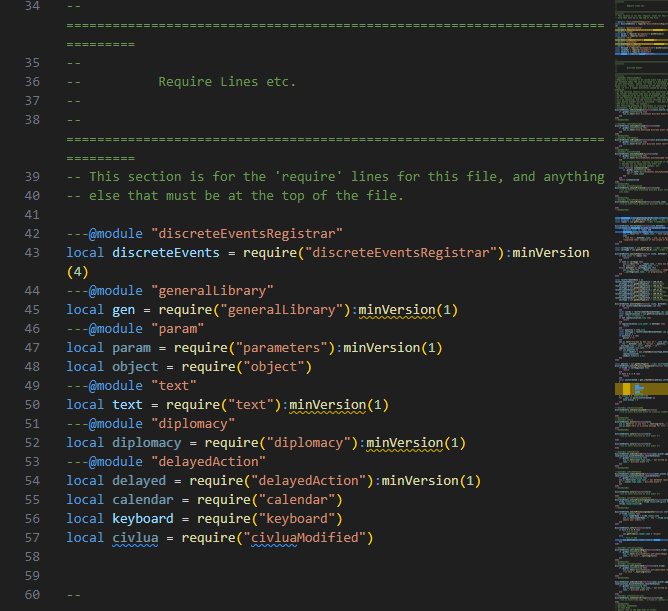

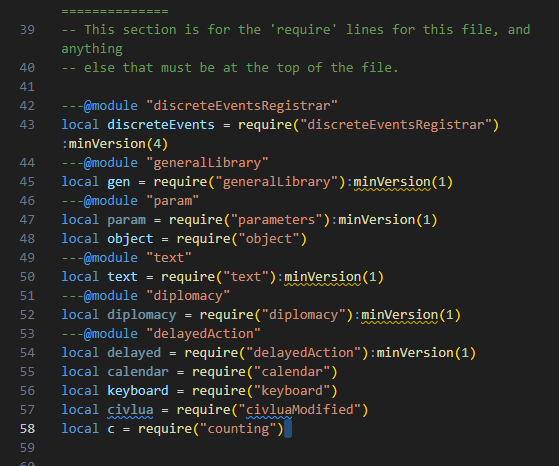

Change tabs to look at discreteEvents.lua, and scroll to the top. There is a section called “Require Lines etc.”, which is a place to use the require function and anything else that should go at the top of the file.

At the end of this section, add the line

local c = require("counting")

This code takes the table returned by counting.lua and assigns it to the local variable c in this file. Using count instead of c would have been normal, but I wanted to make it clear that you can use any name.

The argument for the require function is the file name of the file you want, except that you omit the .lua from the end.

In the Lua Scenario Template, the require function will look in 5 folders for the file specified: The main scenario folder (ClassicRome in this example), EventsFiles, LuaCore, LuaParameterFiles, and MechanicsFiles. If you want to place a file in a different folder, you should give the path relative to one of these five folders. For example, require("Scripts\\PolygonScript) would reference the Scripts\PolygonScript.lua file.

The require function will only execute a file once, even if several files ask for it.

Now, scroll back down to the key press event that we worked with in the previous section (approximately line 430). Re-write the event with the following contents:

discreteEvents.onKeyPress(function(keyCode)

if keyCode ~= keyboard.backspace then

return

end

local tribe = civ.getCurrentTribe()

local activeUnit = civ.getActiveUnit()

if not activeUnit then

return

end

local number = c.units(activeUnit.type,tribe)

civ.ui.text("The "..tribe.name.." have "..number.." "..activeUnit.type.name.." units.")

end)

With this event, pressing Backspace will display a message showing how many of the currently active unit are owned by the current tribe.

The first few lines should be familiar by now.

local tribe = civ.getCurrentTribe()

local activeUnit = civ.getActiveUnit()

The function civ.getCurrentTribe returns the currently active tribe when called. Similarly, civ.getActiveUnit returns the currently active unit, or nil if there is no unit active.

if not activeUnit then

return

end

If no unit is active, we want this event to do nothing.

local number = c.units(activeUnit.type,tribe)

Using our count.units function, referred to here as c.units because of how we required counting.lua, we get the count of the units.

civ.ui.text("The "..tribe.name.." have "..number.." "..activeUnit.type.name.." units.")

This is pretty standard message code like we’ve seen before.

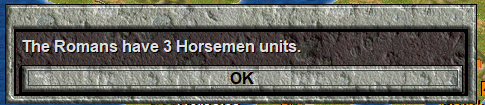

Trying out this event gives:

We don’t need to return a table for require. Sometimes, we may just want to require a file in order to make sure the file is executed when we load a game. A good example is if we want to put some events in their own file for organizational reasons.

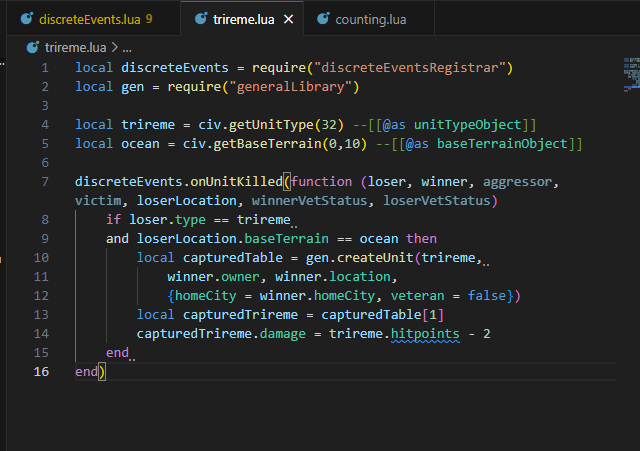

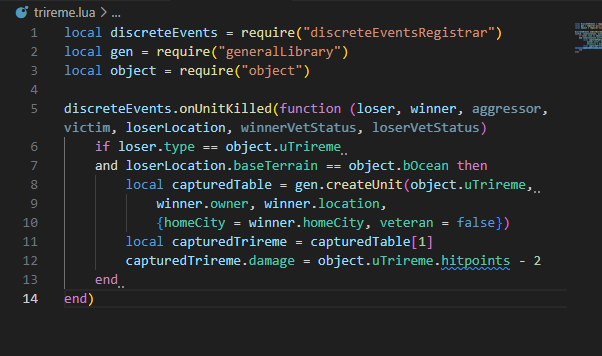

Let’s create trireme.lua in the ClassicRome folder. We’re going to register trireme related events in this file, so we begin by requireing discreteEventsRegistrar.lua:

local discreteEvents = require("discreteEventsRegistrar")

We’re also going to need the General Library in order to use gen.createUnit.

local gen = require("generalLibrary")

Let’s create an event to “capture” a defeated trireme, if the trireme is at sea:

local trireme = civ.getUnitType(32) --[[@as unitTypeObject]]

local ocean = civ.getBaseTerrain(0,10) --[[@as baseTerrainObject]]

discreteEvents.onUnitKilled(function (loser, winner, aggressor, victim, loserLocation, winnerVetStatus, loserVetStatus)

if loser.type == trireme

and loserLocation.baseTerrain == ocean then

local capturedTable = gen.createUnit(trireme,

winner.owner, winner.location,

{homeCity = winner.homeCity, veteran = false})

local capturedTrireme = capturedTable[1]

capturedTrireme.damage = trireme.hitpoints - 2

end

end)

local trireme = civ.getUnitType(32) --[[@as unitTypeObject]]

local ocean = civ.getBaseTerrain(0,10) --[[@as baseTerrainObject]]

Here, we’re giving human readable names to civ objects, as we’ve done before.

discreteEvents.onUnitKilled(function (loser, winner, aggressor, victim, loserLocation, winnerVetStatus, loserVetStatus)

The unit killed in combat execution point registers a function with 7 parameters. The loser is the unit that was killed in combat, while the winner is the unit that was victorious. The aggressor is the unit that attacked, while the victim is the unit that was attacked.

The loserLocation is the tile where the loser was before combat. This is provided because loser.location is sometimes a “tile” which is off of the map, which can cause errors. winnerLocation is not provided because winner.location is always a valid tile.

winnerVetStatus and loserVetStatus give the veteran status of the combatants before combat took place.

Most of these function parameters will remain unused in most of your events, but they are there if necessary.

if loser.type == trireme

and loserLocation.baseTerrain == ocean then

This checks if the loser is a trireme and if the defeat happened on an ocean tile. In this example, I’m enclosing the event in the body of the if statement, instead of returning when conditions are not met.

local capturedTable = gen.createUnit(trireme,

winner.owner, winner.location,

{homeCity = winner.homeCity, veteran = false})

local capturedTrireme = capturedTable[1]

gen.createUnit returns a table of the units produced, so we must get the first element of the capturedTable in order to get the capturedTrireme.

A trireme is the unit type we want to create, the winner’s tribe should own it, so we use winner.owner to get that information. We want the “captured” trireme to be created on the tile of the unit that captured it, which we can get with winner.location. In the options, we set homeCity = winner.homeCity so the new trireme is homed to the same city that supports the trireme that captured it. veteran = false means that the new trireme won’t be a veteran. This wasn’t necessary, since that non-veteran is the default behaviour anyway.

capturedTrireme.damage = trireme.hitpoints - 2

Since the trireme was captured in combat, it makes sense to heavily damage it. I’ve decided that the trireme should have 2 hitpoints, but the unit.hitpoints field can’t be assigned a new value (it is “get” only). We have to set the amount of damage a unit has instead. Since we have a “goal” of 2 hitpoints, we get the maximum hitpoint value using unitType.hitpoints, and subtract 2.

Save trireme.lua, reload the game, and try to trigger this event. You will find you can’t.

The reason for this is that we haven’t called require on this file. So, as far as Lua is concerned, trireme.lua is just an extra file that doesn’t do anything. In order for a file to do something, it must be required by events.lua, or by a file which is itself required by events.lua. (A longer “chain” of requires is also permissible.)

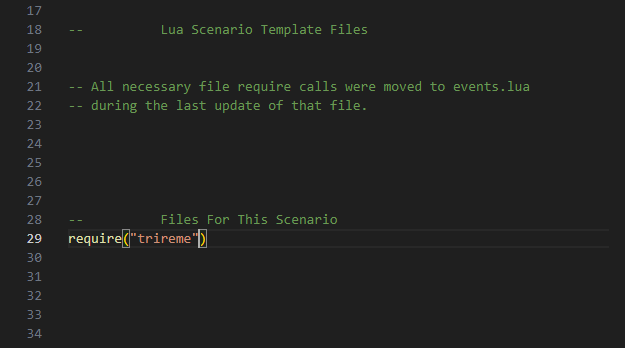

So, we have to execute require("trireme") in at least one file. Any file would be fine, but MechanicsFiles\registerFiles.lua is set aside for this purpose. Sometimes files supplied by the Lua Scenario Template will be registered in this file, so that events.lua doesn’t have to be updated so much. However, at the time of writing, this MechanicsFiles\registerFiles.lua doesn’t register any Template file.

In this file, call require for trireme.lua, save, and try the event again.

This time, the event works. Note that, since we don’t need a table from trireme.lua, we don’t have to assign the returned value of require to anything.

object.lua and the Object Table 🔗

Thus far, when we’ve been writing events, we’ve often created variables with human readable names to represent a specific unitTypeObject or tribeObject. Here are some examples:

local lilybaeum = civ.getTile(41,53,0).city --[[@as cityObject]]

local syracuse = civ.getTile(44,56,0).city --[[@as cityObject]]

local romans = civ.getTribe(1) --[[@as tribeObject]]

local carthaginians = civ.getTribe(2) --[[@as tribeObject]]

local carthage = civ.getTile(36,62,0).city --[[@as cityObject]]

local trireme = civ.getUnitType(32) --[[@as unitTypeObject]]

local ocean = civ.getBaseTerrain(0,10) --[[@as baseTerrainObject]]

There are two problems with this technique. The first is that it using local variables means we need to re-create this code in every file where we want to reference a particular item. The second problem is that this process is error prone, since we have to get the ID numbers exactly right.

The LuaParameterFiles\object.lua file solves both these problems. By consolidating this kind of information into a single file, the “names” of items only have to be decided once. Also, since the Lua Scenario Template provides a script to build this file, the chances of mistakes are greatly diminished. I’ll discuss how to build the object.lua file in a future lesson. For now, we will just use the one I provided with the ClassicRome scenario.

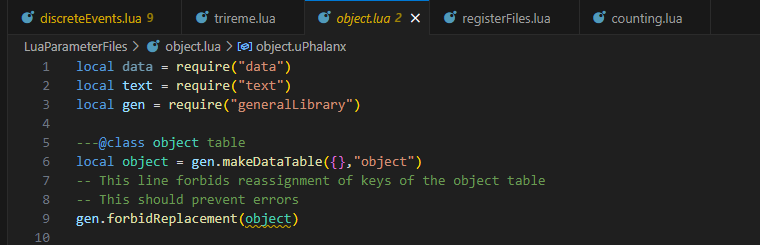

There are a couple require lines, which are necessary to make stuff work.

This section defines the object table. However, instead of using an “ordinary” table, the gen.makeDataTable function creates a special kind of table (which I named a dataTable). The dataTable uses metatable techniques to allow it to be given special properties. (Earlier in this lesson, I mentioned that metatables change the rule of how tables work, but that I wouldn’t be discussing them.)

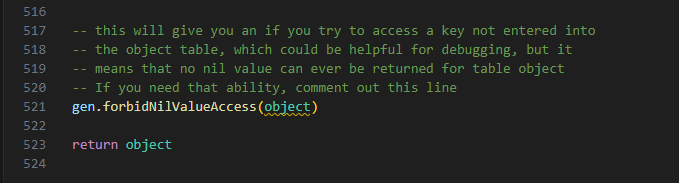

The gen.forbidReplacement function, for example, causes an error if you change a key’s value after it has been assigned. The gen.forbidNewKeys function prevents you from assigning new key-value pairs to a table, and gen.forbidNilValueAccess stops you from trying to get the value from a key if that value is nil. Depending on the use of the dataTable, these features can catch typos or accidental misuse of a table that is supposed to be storing data for your scenario. Despite the fact that object is a dataTable, I’ll usually just refer to it as the “object table.”

The annotation

---@class object table

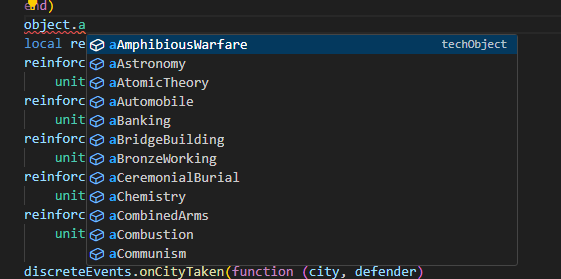

defines the new object dataTable as a custom “class,” similar to a unitObject or tribeObject for the purposes of the Lua Language Server. This improves VS Code’s autocompletion for the object table, even though it makes Lua LS think object is not a valid argument for gen.forbidReplacement.

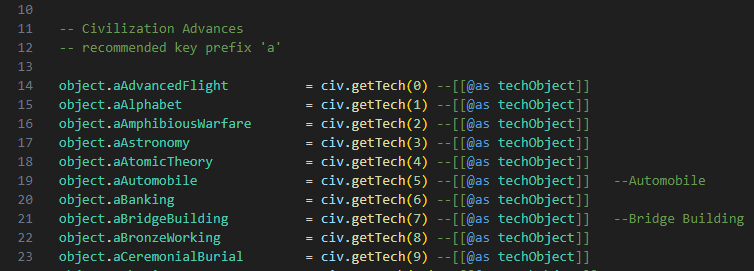

The first section of object.lua lists the Civilization advances:

The keys of object which correspond to a techObject have a as the first letter, for “advance” (t is used elsewhere). This serves two functions. The first is that it makes it easier to preserve the naming convention of the first “word” of a variable name being all lower case, while subsequent words in the name start with an uppercase letter. Second, and more importantly, it provides a clue as to the kind of object it is and makes it easier for autocomplete to suggest the name you want.

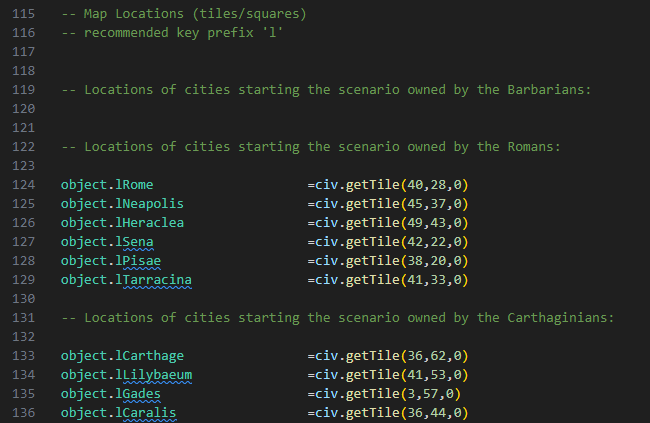

The next section of object.lua is the section for noteworthy tileObjects. These keys are prefixed with the letter l, for “location.”

The script to generate object.lua provides the locations of all cities that exist at the time the script is run. These are organized according to the tribe that owned the cities at the time.

It is likely that you will want to add additional noteworthy locations to this section as you build your scenario.

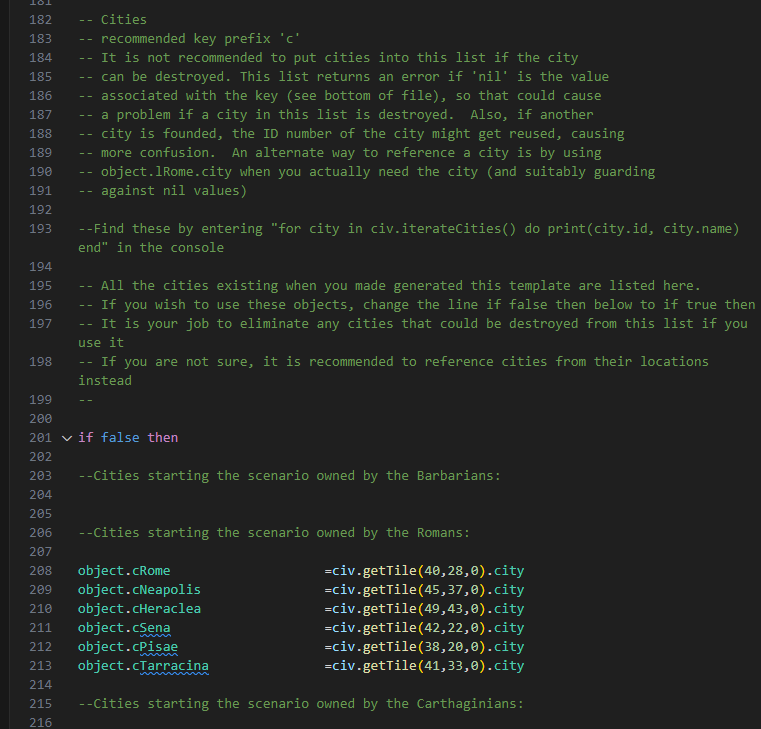

Next, we have the list of all the cityObjects that existed when the script was run. The keys are prefixed with a c.

This section is special. Note line 201 in the picture:

if false then

The cities section is disabled by default in the object.lua file. The reason is that in a standard game of Civilization II, cities can get destroyed. That means that, subsequently, the corresponding key in the object table will be nil. However, at the end of this file, the object table is modified to produce an error if a nil value key is indexed (in order to catch typos).

If you’ve changed @COSMIC2 keys ‘CityPopulationLossAttack’ and ‘CityPopulationLossCapture’ to prevent city destruction, then simply change false to true and you can use this section. Depending on the nature of your scenario, you may also have to consider if cities could be disbanded or starved away.

You could also remove the call to gen.forbidNilValueAccess at the end of this file, and actively check to make sure the relevant cities still exist.

If city destruction is on the table, the recommended way to reference a city is with the city’s location. E.g. object.lRome.city instead of object.cRome. Of course, your code should check and handle the case that the city no longer exists.

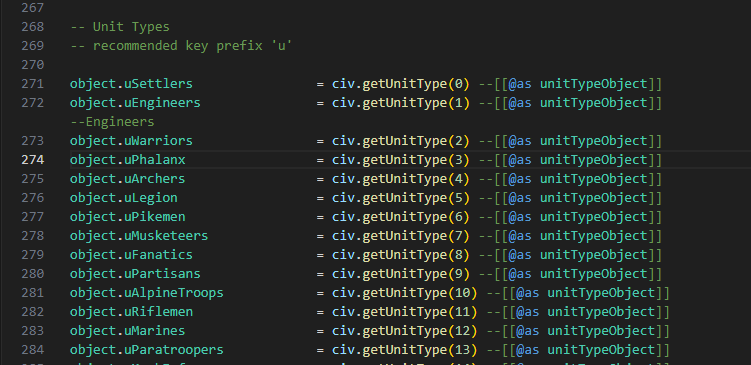

The next section is the list of unitTypeObjects, which are prefixed with u. (Since units are frequently created and destroyed, there is no list of unitObjects.)

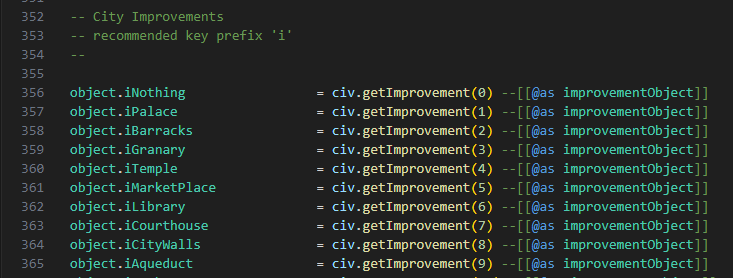

The city improvements, prefixed with i are next.

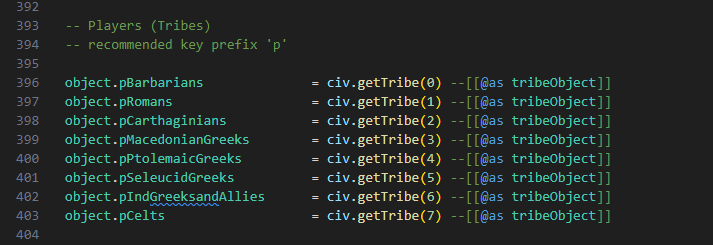

Next comes the list of tribes, prefixed with p for “player.”

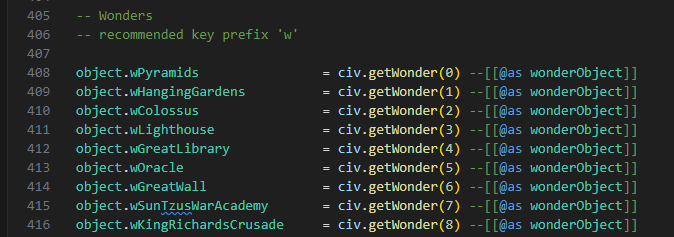

Then, wonders of the world, prefixed with w.

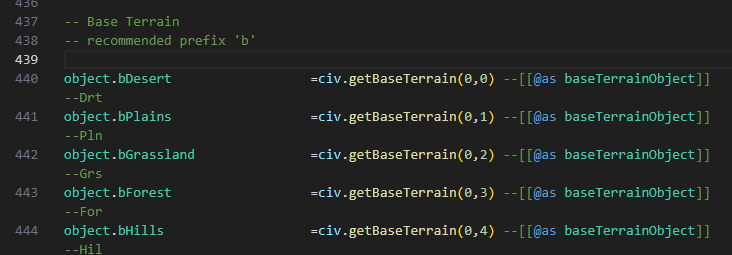

The baseTerrainObjects are prefixed with b.

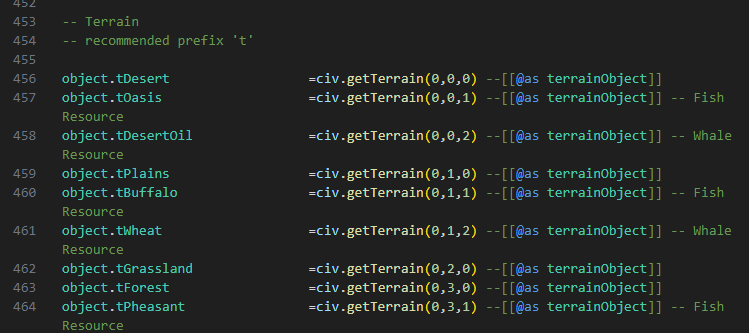

The t prefix, which could fit so many kinds of objects, goes to the terrainObject.

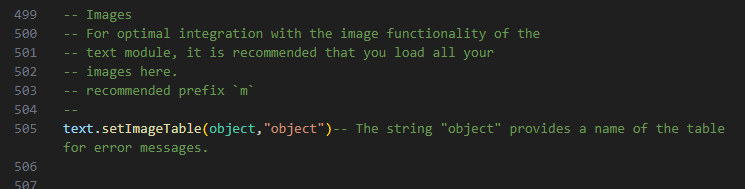

You may find it convenient to keep some text in the object.lua file. If so, you should prefix it with x. In a future lesson I will discuss how to make a message string that doesn’t have to be broken up into little bits.

In a future lesson, I’ll explain how to add images to scenario text boxes. In Lua, these images are represented by imageObjects, which can be stored in the object table, with m as the recommended prefix.

In a future lesson, I’ll discuss the data module. You may find it convenient to place some definitions related to that module here.

Here, we’ve reached the end of the file, where you may decide to comment out gen.forbidNilValueAccess as I mentioned in the cities section.

Now that we understand how to use the object.lua file, go to trireme.lua and use the object table to replace the trireme and ocean variables that are currently being used in that file.

Your code should work after you remove the trireme and ocean local variables.

Expand to see modified version of trireme.lua

and and or “Short Circuiting” 🔗

Let’s look at one of the events in discreteEvents.lua (approximately line 133):

discreteEvents.onCityTaken(function(city,defender)

if (city == lilybaeum or city == syracuse) and

syracuse.owner == romans and

lilybaeum.owner == romans then

civ.ui.text("The "..romans.name.." have captured "..city.name..

" from the "..defender.name.." and, in so doing, have "..

"completed their conquest of the island of Sicily.")

end

end)

Before we re-write the event to use the object table, let’s test out the event if a city is missing, which could happen if it is destroyed. Destroy Lilybaeum. Press CTRL+SHIFT+D to destroy all the units on the tile. Then, press SHIFT+D to disband the city.

Save this game (using a different name), and then load the game.

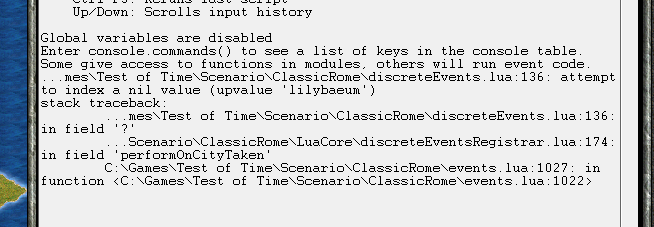

Now, use Roman units to capture Syracuse. You will get the following error:

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:136: attempt to index a nil value (upvalue 'lilybaeum')

stack traceback:

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:136: in field '?'

...Scenario\ClassicRome\LuaCore\discreteEventsRegistrar.lua:174: in field 'performOnCityTaken'

C:\Games\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\events.lua:1027: in function <C:\Games\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\events.lua:1022>

This is the heart of this message:

...mes\Test of Time\Scenario\ClassicRome\discreteEvents.lua:136: attempt to index a nil value (upvalue 'lilybaeum')

The term “indexing” refers to asking for the value associated with a key. So, myTable["myKey"] is “indexing” myTable, as is myTable.myKey. So, the phrase “attempt to index a nil value” means that our code is trying to get a value associated with a key from nil. This obviously isn’t allowed, so we get an error.

Since the upvalue (local variable) is lilybaeum, that means that lilybaeum is a nil value. It is defined on line 129:

local lilybaeum = civ.getTile(41,53,0).city --[[@as cityObject]]

When we re-loaded the game, the tile (41,53,0) no longer had a city on it. Therefore, civ.getTile(41,53,0).city was nil, and lilybaeum was set to nil. Then, line 136 was evaluated during our event:

lilybaeum.owner == romans then

The variable lilybaeum is indexed with the key owner, which causes an error since lilybaeum is actually nil.

Now, let’s re-write the event using the object table. We’re going to make this event robust to the possibility that one or both of Lilybaeum and Syracuse are destroyed. The event won’t take place in that instance, but we won’t get an error.

discreteEvents.onCityTaken(function(city,defender)

if city.location ~= object.lLilybaeum and

city.location ~= object.lSyracuse then

return

end

if object.lLilybaeum.city and

object.lLilybaeum.city.owner == object.pRomans

and object.lSyracuse.city and

object.lSyracuse.city.owner == object.pRomans then

civ.ui.text("The "..object.pRomans.name.." have captured "..city.name..

" from the "..defender.name.." and, in so doing, have "..

"completed their conquest of the island of Sicily.")

end

end)

Let’s begin with

if city.location ~= object.lLilybaeum and

city.location ~= object.lSyracuse then

return

end

This section of code replaces the check that (city == lilybaeum or city == syracuse). Since we haven’t assigned cityObject keys in the object table, we have to rely on tiles instead. It is easy to compare city.location to the tiles where those cities are supposed to be. If the captured city is not on either tile, the event should not take place, therefore the function returns.

if object.lLilybaeum.city and

object.lLilybaeum.city.owner == object.pRomans

and object.lSyracuse.city and

object.lSyracuse.city.owner == object.pRomans then

We’re looking to check these two conditions

syracuse.owner == romans and

lilybaeum.owner == romans then

However, simply checking object.lLilybaeum.city.owner == object.pRomans has the exact same flaw as lilybaeum.owner == romans. Before trying to evaluate object.lLilybaeum.city.owner, we must first establish that object.lLilybaeum.city is not nil. We can do this because the and (as well as or) operator “short circuits” when evaluating.

What does this mean? Well, in lesson 4 I explained how the and and or operators “combined” true and false values. I said that a and b returns true if both a and b are true, and false otherwise. I also said that a or b returns true if one or both of a and b are true, and returns false only if both a and b are false.

This is correct when a and b are boolean values, but it is not the whole truth about and and or. The actual definition of and is that a and b returns a if a is falsy, otherwise it returns b. So,

7 and false --> false

false and 7 --> false

nil and false --> nil

false and nil --> false

7 and 8 --> 8

true and "spain" --> "spain"

Similarly, a or b returns a if a is truthy, otherwise, it returns b.

7 or false --> 7

false or 7 --> 7

nil or false --> false

false or nil --> nil

true or 7 --> true

7 or true --> 7

7 or 8 --> 7

Where does “short circuiting” come in? Well, in most cases, Lua will evaluate all arguments to a function or operator before executing the function or operator itself. However, and and or are different. If the a value will be returned, then b is never looked at or evaluated. Now, have a look at this expression:

object.lLilybaeum.city and object.lLilybaeum.city.owner == object.pRomans

If object.lLilybaeum.city is nil, then object.lLilybaeum.city.owner will generate an error, which we don’t want. However, because of short circuiting, if object.lLilybaeum.city is nil, Lua will not try to evaluate object.lLilybaeum.city.owner == object.pRomans, and, so, no error will be caused. So, the section of code,

if object.lLilybaeum.city and

object.lLilybaeum.city.owner == object.pRomans

and object.lSyracuse.city and

object.lSyracuse.city.owner == object.pRomans then

checks first if object.lLilybaeum.city is truthy. If not, the falsy nil is returned, and the if statement is not exectued.

If it is truthy, object.lLilybaeum.city.owner == object.pRomans is evaluated. The only way for object.lLilybaeum.city to be truthy is for it to be a city, therefore, object.lLilybaeum.city.owner will not cause an error.

If object.lLilybaeum.city.owner == object.pRomans is true, we move on to checking if object.lSyracuse.city is truthy. If it isn’t, we stop and the if statement doesn’t execute. If it is, object.lSyracuse.city.owner == object.pRomans can be evaluated without causing an error.

The final section of this event code is the body of the if statement.

civ.ui.text("The "..object.pRomans.name.." have captured "..city.name..

" from the "..defender.name.." and, in so doing, have "..

"completed their conquest of the island of Sicily.")

Here, the local variable romans has simply been replaced with object.pRomans.

Using Global Variables 🔗

So far in this lesson, I haven’t had good things to say about global variables. The closest I’ve come is the fact that they must be used in the Lua Console, which could be taken as a criticism of the Console.

Well, most of the “treachery” of global variables comes from the fact that Lua makes it easy to use them by accident. When used on purpose, global variables make it easy to share variables between files.

But, you may say, we can use require to share data between files. Why bother with global variables? The answer I have is that require makes sharing relatively easy in one direction, but it requires some work if you want to share in the other direction.

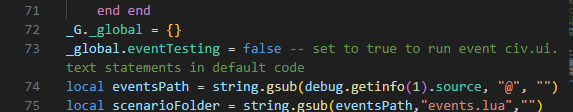

For example, in events.lua, I defined the global variable _global.eventTesting:

Many of the sample events are structured like this:

discreteEvents.onBribeUnit(function(unit,previousOwner)

if _global.eventTesting then

civ.ui.text("Bribe unit discrete event test")

end

end)

If I change the value of _global.eventTesting to true in events.lua, I can easily test whether events are working if I make substantial changes to the template. (The alternate method is to uncomment tests and hope I remember to comment them out again when I’m finished.)

Since discreteEvents.lua is required by events.lua, it can’t require events.lua itself. Therefore, the value of an “eventTesting” variable couldn’t be passed through a table provided by require. There is a way to “pass back” information without using global variables, but it is more work, and I won’t discuss it now.

In case it wasn’t obvious by the _global.eventTesting example, the Lua Scenario Template provides global variables through use of the _global table. _global is a “real” global variable (a key in the _G table), so you can use it in any file without a require line, like you can do with print.

If you want to assign a value to a global variable, you assign a key and value like you would any other table:

_global.myVariable = "myValue"

and to use it, you simply index the _global table:

print(_global.myVariable)

You can use the console table in the same way as the _global table. console is another “real” global variable, and you can assign key-value pairs to it. I think I’ve only assigned the eventTesting variable to _global, but I assign stuff to the console table that I anticipate would be useful in the Lua Console.

If, for some reason, you find it desirable or necessary to use a “true” global variable, you can add a new key to the _G table by using the rawset function:

rawset(table,key,value)

Initializing myGlobalVariable to 10 would be done like this:

rawset(_G,"myGlobalVariable",10)

This works because the rawset function ignores “metatables” (the feature that changes table behaviour, which I won’t explain here) when assigning a value to a table key.

The gen.original and gen.constants Table 🔗

Earlier in this lesson, we learned how to use the object table from object.lua in order to make our code more readable. Sometimes, however, code will be more understandable if we use the a name for the object corresponding to its name in the original game. If this is the case, the General Library has a table similar to the object table called gen.original.

For example, it may make more sense for your code to reference the technology giving access to the “Communism” government type as

gen.original.aCommunism

instead of, say,

object.aTwinMonarchy

Even if you don’t find it convenient to use the gen.original table yourself, you should be aware of it because when I write examples for settings modules, I use the gen.original table instead of the object table.

This is the reference page for the gen.original table.

The General Library also includes another useful reference table, the gen.constants table, with this reference page. There are many fields for civ objects that have integer values which represent a list of possible options, rather than numbers. For example, a unitTypeObject has these fields:

domain 🔗

unitTypeObject.domain --> integer(get/set - ephemeral) Returns the domain of the unit type (0 - Ground, 1 - Air, 2 - Sea).

role 🔗

unitTypeObject.role --> integer(get/set - ephemeral) Returns the role of the unit type.

For these fields, and others like them, making checks like

if unit.type.role == gen.c.roleSettle then

if unit.type.domain ~= gen.c.domainAir then

if tech.epoch == gen.constants.categoryMilitary then

is more readable and less error prone than

if unit.type.role == 5 then

if unit.type.domain ~= 1 then

if tech.epoch == 0 then

The gen.constants table also includes some other noteworthy integers, such as gen.c.maxTechID.

This table is a relatively recent innovation, so if you’re looking through older code that I’ve written, you will still find a lot of “magic” integers that have no context. If you notice an omission of a noteworthy number, feel free to let me know.

Methods and require("someModule"):minVersion(4) 🔗

Earlier in this lesson, we learned the following way to use the require function:

local object = require("object")

This syntax is adequate, unless you plan to write Lua code for others. However, since I wrote the Lua Scenario Template for others to use, you will sometimes come across a slightly different syntax.

If you scroll to the top of discreteEvents.lua, you will find some require lines with the following form:

---@module "discreteEventsRegistrar"

local discreteEvents = require("discreteEventsRegistrar"):minVersion(4)

The purpose of this different syntax is to cause an error if you have outdated files. Since the Lua Scenario Template is a work in progress, I sometimes update modules or provide entirely new ones. It is pretty easy to give someone an updated file, if they want to use a feature that didn’t exist when they started building their scenario.

What isn’t so easy, however, is making sure that all the dependencies are updated. Sometimes, adding new features to a module involves updating another module, such as the General Library. Having an outdated version of the General Library will eventually produce an error when the new module asks for a function that isn’t in the obsolete version, but that probably won’t be right when the scenario is loaded.

It is much more convenient to be told right away that a file is obsolete, but the require function doesn’t have any sort of version check. I therefore had to implement this myself, and the syntax :minVersion(version) seemed to be the best. (There is also a :recommendedVersion(version) syntax, which I seldom use.)

The : character is used for methods. A method is just a kind of function, but where one of the function arguments is the item just before the :. The cityObject has several methods associated with it. Here are a few of them:

addImprovement 🔗

(method) cityObject:addImprovement(improvement: improvementObject)Alias for

civ.addImprovement(city, improvement).

hasImprovement 🔗

(method) cityObject:hasImprovement(improvement: improvementObject) -> boolean: booleanAlias for

civ.hasImprovement(city, improvement).

removeImprovement 🔗

(method) cityObject:removeImprovement(improvement: improvementObject)Alias for

civ.removeImprovement(city, improvement).

relocate 🔗

(method) cityObject:relocate(tile: tileObject) -> boolean: booleanRelocates the city to the location given by

tile. Returnstrueif successful,falseotherwise (if a city is already present for example).

Open the Lua Console in a ClassicRome saved game, and enter the following code to move Rome to an adjacent square:

civ.getTile(40,28,0).city:relocate(civ.getTile(39,29,0))

Let’s break down this line. Since this is a method, the form is cityObject:relocate(tileObject). Note the : between cityObject and the name of the method, relocate.

Before executing this command, Rome is located on the tile (40,28,0), so, in order to get the cityObject that we want, we call civ.getTile(40,28,0).city to get the Rome cityObject. We call civ.getTile(39,29,0) to get the tileObject that is the destination. Put it all together, and we get the code to move Rome southwest by one tile.

While the relocate method returns a boolean to tell you if the relocation was successful, the minVersion method returns the the same table that called it. This way, it can simply be appended to the require line. Unfortunately, the Lua Language Server doesn’t realize that the minVersion method returns the table that was originally required, so I had to add the ---@module annotation (e.g. ---@module "discreteEventsRegistrar") on the previous line so that autocomplete and tooltips would work properly. Sometimes LuaLS underlines the minVersion method in yellow. I presume this is because the method is created via a function (rather than explicitly defined), but I don’t know why it is inconsistent at the time of writing this.

Although writing functions is very common, writing methods is quite rare, so I won’t explain how to give a table a method now.

Conclusion 🔗

In this lesson, we’ve learned about variable scope and global variables. As part of the discussion, we analysed how code executes in a particularly detailed way. Determining why code doesn’t behave the way we want it to will sometimes require this kind of analysis, but it is rare to have to be quite so painstaking. We have also analysed several error messages as part of this discussion.

In this lesson, we have also learned about the require function and how to use it to share information between files. I also showed you the object.lua file and how to use it to make your files more readable. As part of that process, we build a counting function and an event to “capture” triremes.

We also discussed the “index a nil value” error and how to avoid them using the “short circuiting” property of the and and or operators.

Finally, we discussed object methods and how to use them.

As always, if you have any questions or feedback for this lesson, you can post it in this thread.

| Previous: Loops and Tables | Next: |